How Long Does It Take for the Moon to Orbit the Earth

This is the 26th in an exclusive series of 50 articles, one published each day until July 20, exploring the 50th anniversary of the first-ever Moon landing. You can check out 50 Days to the Moon here every day .

Buzz Aldrin, the Apollo 11 lunar module pilot, was the second human being to set foot on the Moon. For the first 30 minutes of his Moon walk with Neil Armstrong on Sunday night, July 20, 1969, he knocked around in his spacesuit, doing the tasks that needed doing, including helping Armstrong get the first American flag planted and unfurled.

But after about 30 minutes on the Moon, Aldrin started to have a little fun. He started to race around Tranquility Base, testing out his speed and maneuverability in one-sixth lunar gravity and a bulky-but-flexible spacesuit.

He ran straight at the video camera full-tilt, explaining that running like he was at that moment was a little dangerous, because it was hard to find your footing and maintain your balance on the Moon, and you might just fall right on your face.

He did quick cuts left and right, planting a foot and changing direction like an NFL running back dodging tacklers.

He did kangaroo hops right past the American flag, but observed that kangaroo hops weren't, after all, a particularly good way of getting around the Moon.

The whole world was watching and listening to Aldrin's Moon antics—94% of U.S. homes were tuned to the Moon walk, along with 600 million people worldwide—but one person in particular was riveted, and also increasingly fretful: A man named Sonny Reihm, who was in a Mission Control support room in Houston, and was the project leader for spacesuits at the company that made them: Playtex.

Reihm had started at the industrial division of Playtex back in 1960, at age 22, and by the time of the 1969 Moon landing, he was head of the team that designed, sewed, tested, and then custom-tailored the spacesuits the Apollo astronauts would wear. Playtex, which brought America the Cross-Your-Heart bra in the 1950s and '60s, had sold the talent of its industrial division to NASA in part with the cheeky observation that the company had experience designing garments that had to be both form-fitting and flexible. (That division of Playtex, ILC Dover, is independent now, and still makes all of NASA's spacesuits.)

Aldrin's antics made Reihm nervous. Not because there was anything to worry about—Apollo spacesuits were 21 layers of nested fabric, strong enough to stop a micrometeorite, while flexible enough for Aldrin's kangaroo hops—but those were Reihm's spacesuits; he knew how many things could go wrong, and didn't want to be responsible for any Moon-walk mishaps.

"That silly bastard is out there running all over the place," is what Reihm was thinking as he watched Aldrin's cavorting.

We're not used to thinking of the astronauts as exuberantly rejoicing in being on the Moon, because a lot of what we've seen and heard of the Apollo missions is pretty technical and buttoned-down. But there were plenty of uninhibited moments, too, starting right at the beginning.

Armstrong and Aldrin, in fact, were scheduled for a five-hour nap shortly after they landed and secured the lunar module. But they told Mission Control they wanted to ditch the nap, suit up, and get outside.

They hadn't flown to the Moon to sleep.

Reihm's anxiety—shared by other members of the spacesuit team who were also watching Aldrin and worrying about him improbably causing a tear or a leak in the suit—is a reminder that looking back, we know how the story came out. At the time, the men and women responsible for creating all the spaceflight technology didn't know that everything would work almost perfectly.

Reihm remembers that all he could think, watching Aldrin, was: "Please go back up that ladder and get back into the safety of that lunar module. When [they] went back up that ladder and shut that door, it was the happiest moment of my life. It wasn't until quite a while later that I reveled over the accomplishment."

As subsequent Moon landings lasted days instead of hours, as the Moon walks got longer, as NASA and the astronauts gained more experience and confidence, there was less fretting.

Here's a video of the astronauts being exuberant, silly, and sometimes simply cheerfully clumsy on the Moon. It's a compilation, with the one flaw being that the astronauts are not identified by name. It's a wonderful reminder that astronauts are human, too, and that, yes, space travel is, in addition to everything else, a rocket-ride of fun.

Here are a couple more moments of fun on the Moon:

Apollo 14 commander Alan Shepard used a makeshift six-iron to take the first golf swings on the Moon, what he called "a little sand-trap shot," on February 6, 1971:

Apollo 15 commander Dave Scott performed a version of Galileo's famous experiment about falling objects and gravity, on August 2, 1971, using a feather and geology hammer, because, Scott said, "One of the reasons we got here today was because of a gentleman named Galileo."

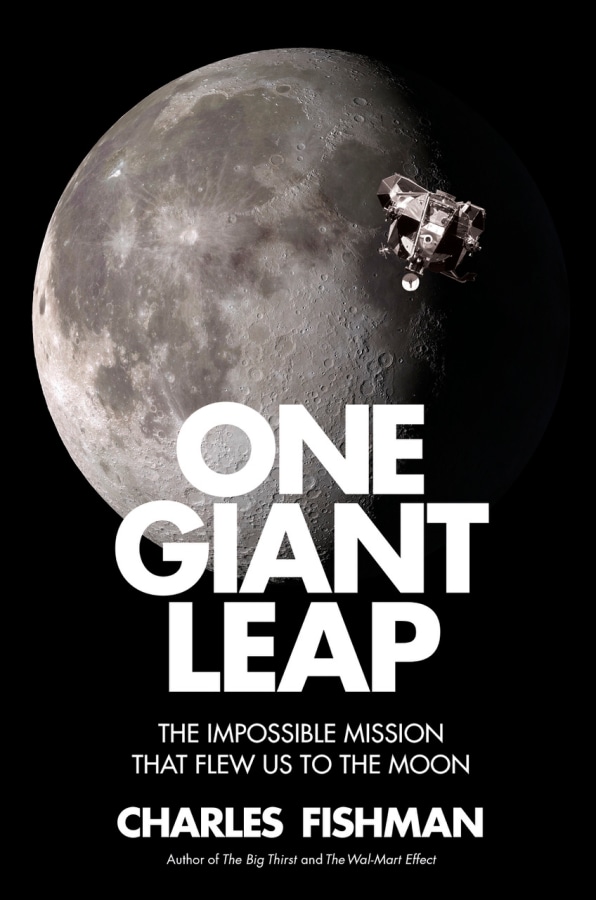

Charles Fishman, who has written for Fast Company since its inception, has spent the past four years researching and writing One Giant Leap, his New York Times best-selling book about how it took 400,000 people, 20,000 companies, and one federal government to get 27 people to the Moon. (You can order it here.)

For each of the next 50 days, we'll be posting a new story from Fishman—one you've likely never heard before—about the first effort to get to the Moon that illuminates both the historical effort and the current ones. New posts will appear here daily as well as be distributed via Fast Company's social media. (Follow along at #50DaysToTheMoon).

How Long Does It Take for the Moon to Orbit the Earth

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/90369175/astronauts-had-fun-on-the-moon-and-people-on-earth-fretted-about-it

0 Response to "How Long Does It Take for the Moon to Orbit the Earth"

Post a Comment